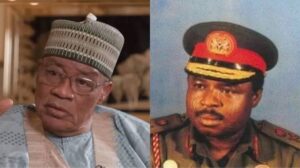

Former military leader, General Ibrahim Babangida (retd.), has opened up about the failed coup allegedly orchestrated by his lifelong friend, General Mamman Vatsa, explaining the painful choice he faced between personal loyalty and national security.

In his newly released autobiography, A Journey of Service, launched on February 20, 2025, Babangida popularly known as IBB shares his perspective on the events that led to Vatsa’s execution.

He recalls first hearing of the alleged plot through circulating rumours, which he initially dismissed as envy over their close relationship.

In Chapter 10, titled The Challenges of Leadership, Babangida details his consultations with senior officers, including Generals Nasko, Garba Duba, and Wushishi, before ordering covert investigations. These inquiries, he said, produced undeniable evidence of Vatsa’s involvement in financing the coup.

Babangida wrote, “With our experience in the few months in government and the benefit of hindsight based on previous rumours, I determined that the best way to tackle the rumours about a possible Vatsa coup was by confronting the principal suspects.”

He added, “When the decibel of the stories rose too high, I confronted Vatsa himself after reporting the rumours to more senior colleagues like Generals Nasko, Garba Duba and Wushishi. Nasko intervened and tried to find out the truth from Vatsa. Vatsa flatly denied it all, but the covert investigations by the military and other intelligence services continued.”

The investigations, Babangida noted, revealed that Vatsa had provided funds to officers to advance the coup plans. One officer, Lt-Col. Musa Bitiyong, reportedly received N50,000, which Vatsa claimed was for a farming project.

“He admitted it, and Vatsa also admitted the payment but said he wanted to help Bitiyong establish a farm project — the case of Lt-Col. Musa was not helped because he had previously been involved in other controversial coup stories,” Babangida recounted.

The alleged coup plot included plans to bomb Eko Bridge in Lagos, sabotage Air Force operations, and even target the presidential aircraft.

“I felt a deep personal sense of betrayal,” Babangida wrote, reflecting on their shared history dating back to their youth in Minna.

Following a military tribunal’s deliberation, the coup plotters, including Vatsa, were executed in March 1986. Babangida described the decision as both a personal loss and a necessary step to safeguard Nigeria.

“They had planned a bloody coup which would have plunged the country into darkness. I had to choose between saving a friend’s life and the nation’s future,” he wrote.

Despite the emotional weight of the decision, Babangida maintained that preserving national stability outweighed personal grief.

“Of course, Vatsa’s death was a personal loss of a childhood friend. As a human being, I was somewhat depressed to watch him die in such circumstances.

“However, the nation’s stability and the cohesion of the armed forces were too high on the scale of priorities to be sacrificed for personal considerations. The law and the imperatives of order and national security are overriding.”

Babangida also addressed subsequent attempts to politicise the incident, stating that he remained steadfast in his belief that the executions were crucial for the unity of the armed forces and the nation’s future.

He acknowledged that some officers were unhappy with Vatsa’s appointment as Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, as he had not participated in the coup that ousted General Muhammadu Buhari. However, Babangida insisted that he had done his best to preserve their friendship.

“I remained true to our friendship and bent backwards to accommodate his excesses and boisterousness,” he wrote.